Defining the Temperature Threshold That Is Too Hot for Cats

It is a common observation that cats actively seek warmth, often found sunbathing in the window, nestled near heating vents, or lounging on warm asphalt. This behavior is rooted in their evolutionary history and their preferred thermoneutral zone—the ambient temperature range where they do not need to expend energy to maintain their core body temperature. For cats, this zone is significantly warmer than for humans, generally falling between 75°F (24°C) and 80°F (26.7°C), according to veterinary experts.

However, despite their affinity for high temperatures, cats are still susceptible to environmental heat stress. When ambient temperatures rise too high, a cat's intrinsic cooling mechanisms can fail, leading to potentially fatal conditions like heatstroke and severe dehydration. Understanding what temperature is too hot for cats and recognizing the subtle signs of heat distress is paramount for responsible pet ownership.

Establishing the Critical Heat Threshold for Felines

While most healthy, average-weight cats can manage temperatures between 80°F and 90°F (26.7°C–32.2°C) by actively relocating to cooler spots, the consensus among veterinary professionals is that temperatures exceeding 100°F (37.7°C) pose a severe and immediate danger. At this threshold, the risk of developing life-threatening hyperthermia dramatically increases.

It is important to remember that environmental control is their primary defense. Healthy cats will intuitively use conduction—lying on cool surfaces like tile or porcelain—and evaporative cooling—self-grooming to wet their coat with saliva—to dissipate excess heat. However, cats who are older, have existing respiratory conditions, or are housed in restricted environments may lack the capacity to execute these behaviors effectively.

Acute Health Risks Associated with High Environmental Temperatures

Sustained exposure to extreme heat can quickly escalate minor discomfort into critical conditions:

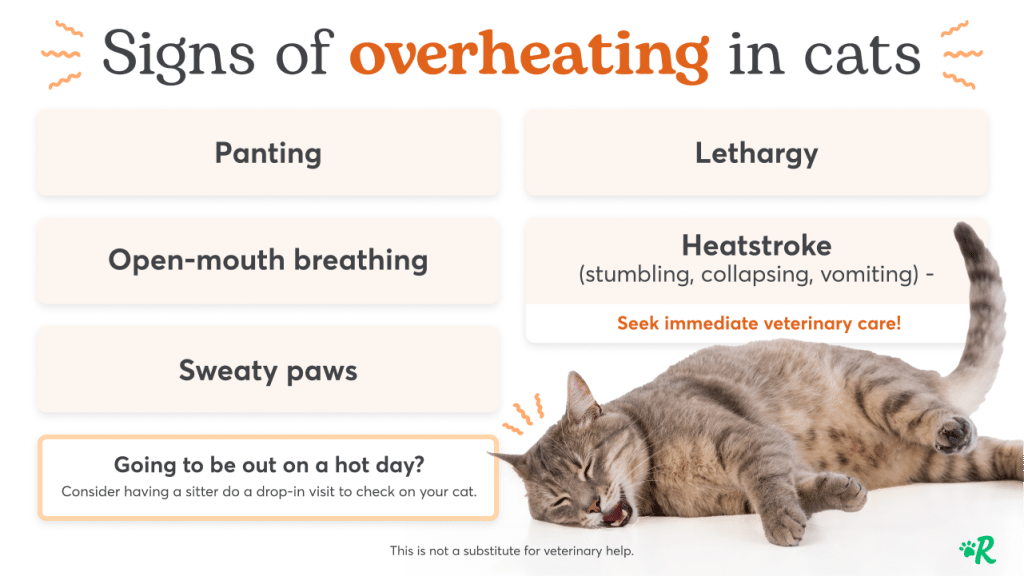

- Overheating (Hyperthermia): This occurs when the cat’s core body temperature exceeds the normal range of 100.5°F–102.5°F. Early signs include lethargy and profuse sweating from the paw pads.

- Dehydration: Elevated temperatures lead to accelerated fluid loss, which strains the cardiovascular and renal systems.

- Heatstroke (Severe Hyperthermia): A body temperature exceeding 104°F (40°C) signals a medical emergency, resulting in multi-organ dysfunction if not immediately cooled.

- Solar Dermatitis (Sunburn): Even at moderate temperatures, prolonged direct sun exposure, particularly on sparsely haired areas like the ear tips and nose bridge, can lead to severe sunburn, increasing the long-term risk of skin cancers (e.g., squamous cell carcinoma), especially in cats with white or light-colored coats.

Recognizing the Advanced Signs of Feline Heat Stress

Cats are masters at masking discomfort. Pet owners must be vigilant for these critical signs, as they indicate that the cat's natural cooling mechanisms are overwhelmed.

Signs Requiring Immediate Action

- Panting or Open-Mouth Breathing: This is a highly abnormal and late-stage defense mechanism in cats. Unlike dogs, a cat panting indicates that the situation is already critical, regardless of the ambient temperature reading.

- Severe Lethargy and Collapse: Extreme weakness, difficulty moving, or losing consciousness.

- Gastrointestinal Distress: Uncontrolled vomiting or severe diarrhea.

- Neurological Signs: Stumbling, incoordination, unresponsiveness, or seizures are hallmarks of central nervous system damage due to profound hyperthermia.

- Profuse Sweating: Noticeable moisture on the paw pads (the only location where cats sweat).

Risk Factors: Why Some Cats Overheat More Easily

Individual predispositions significantly influence a cat's ability to cope with high ambient temperatures:

- Age and Metabolic Rate: Kittens and senior cats possess a diminished capacity for thermoregulation, making them highly vulnerable to sudden temperature fluctuations.

- Breed and Conformation (Expert Augmentation): Brachycephalic breeds (e.g., Persians, Himalayans, Exotic Shorthairs) are at the greatest risk. Their flattened facial structures restrict airflow, making panting an inefficient method for evaporative cooling, which leads to rapid, catastrophic overheating.

- Coat Density: Cats with thick, double coats (e.g., Maine Coons, Norwegian Forest Cats) have superior insulation, which can become detrimental in extreme heat unless they are regularly groomed to remove excess undercoat.

- Obesity: Excess body fat acts as an additional layer of insulation, impeding heat dissipation and straining the cardiovascular system. Maintaining an ideal body condition score is critical for heat tolerance.

- Pre-existing Conditions: Cats with chronic diseases like severe heart disease (e.g., Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy), kidney disease, or respiratory issues (e.g., Asthma) have compromised internal reserves and are less able to tolerate thermal stress.

Heatstroke: Pathophysiology and Long-Term Consequences

When the core body temperature exceeds 104°F, damage to cellular structures begins. Without rapid, correct intervention, heatstroke can lead to severe, irreversible consequences:

- Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC): (The "clotting" mentioned in the source). This is a complex, often fatal condition where high heat causes widespread endothelial damage, leading to the formation of multiple small blood clots throughout the circulatory system. This rapid consumption of clotting factors then results in severe, uncontrolled bleeding from other sites. DIC is a major cause of death in heatstroke victims.

- Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Extreme dehydration and hypotension (low blood pressure) due to heat stress lead to reduced blood flow to the kidneys, potentially causing AKI, which may necessitate lifelong management for subsequent chronic kidney disease.

- Neurological Damage: Profound hyperthermia causes cerebral edema (brain swelling) and electrolyte shifts, directly leading to seizures, permanent brain damage, and chronic neurological deficits.

Veterinary and First-Aid Response

If a cat shows any signs of heatstroke (stumbling, collapse, uncontrollable vomiting), they require immediate emergency veterinary care. Contacting the clinic while en route allows staff to prepare for rapid cooling upon arrival.

First Aid During Transport: Do *not* use ice water. Instead, apply cool (not cold) water or damp towels to the cat’s body, especially the extremities and neck. Offer small amounts of water, but do not force drinking. The primary goal is transportation to a veterinarian where they can administer intravenous (IV) fluids to correct shock and dehydration, and perform careful core temperature lowering.

Proactive Environmental Management Tips

Preventative steps are the most effective strategy against thermal stress:

- Hydration Enhancement: Always provide multiple sources of fresh water, ideally using a cat fountain to encourage intake. Canned food is superior to dry kibble for maintaining hydration.

- Air Conditioning and Ventilation: Use fans or AC to maintain an ambient indoor temperature within the cat's comfort range (ideally below 80°F). Keep blinds and curtains closed during peak sun hours.

- Cooling Surfaces: Place damp towels, specialized cooling mats, or access to non-carpeted floors (tile, stone, tubs) for conductive cooling.

- Grooming: For long-haired breeds, regular brushing to remove the dense undercoat facilitates better air circulation near the skin.

- UV Protection: Apply a veterinarian-approved, non-toxic pet sunscreen to susceptible areas (ears, nose) on white or light-coated cats exposed to sun.

- Outdoor Management: Keep all cats, especially those with high risk factors, strictly indoors during the hottest parts of the day (typically 10 AM to 4 PM).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q: Why is an enclosed space like a car so dangerous for a cat, even for a few minutes?

A: The temperature inside a car, even with a window slightly cracked, can rise by over 20°F (11°C) in just 10 minutes. Because cats have limited cooling mechanisms, this rapid, confined temperature spike creates a hyperthermic oven, leading to fatal heatstroke much faster than in an open environment.

Q: Does humidity affect how hot my cat feels?

A: Yes, humidity is a critical factor. High humidity significantly compromises a cat's ability to use evaporative cooling (panting or saliva grooming) because the air is already saturated with moisture. This makes high-humidity environments, even at moderate temperatures (e.g., 85°F), much more dangerous than dry heat.

Q: What is the single most effective way to protect my cat from overheating in the summer?

A: The most effective preventative measure is providing a consistently air-conditioned environment. Access to an AC unit maintains the ambient temperature well below the critical threshold, mitigating the need for the cat’s often-inefficient biological cooling responses.

Posting Komentar untuk "Defining the Temperature Threshold That Is Too Hot for Cats"